These days, nearly everyone communicates through some kind of keyboard, whether they are texting, emailing, or posting on various internet discussion forums. Talking over the phone is almost outmoded at this point. But only a few decades ago, the telephone was king of real-time communication. It was and still is a great invention, but unfortunately the technology left the hearing and speaking-impaired communities on an island of silence.

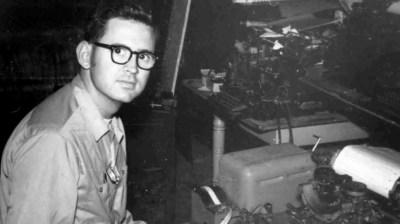

Engineer and professor Paul Taylor was born deaf in 1939, long before cochlear implants or the existence of laws that called for testing and early identification of hearing impairment in infants. At the age of three, his mother sent him by train to St. Louis to live at a boarding school called the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID).

Here, he was outfitted with a primitive hearing aid and learned to read lips, speak, and use American sign language. At the time, this was the standard plan for deaf and hearing-impaired children — to attend such a school for a decade or so and graduate with the social and academic tools they needed to succeed in public high schools and universities.

After college, Paul became an engineer and in his free time, a champion for the deaf community. He was a pioneer of Telecommunications Devices for the Deaf, better known as TDD or TTY equipment in the US. Later in life, he helped write legislation that became part of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

Paul was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2017 and died in January of 2021 at the age of 81. He always believed that the more access a deaf person had to technology, the better their life would be, and spent much of his life trying to use technology to improve the deaf experience.

Learning to Speak Without Hearing

Soon after three-year-old Paul started school at CID, he met a little girl named Sally Hewlett who would one day become his wife. Along with their classmates, they spent the next several years learning to speak by holding their hands to the teacher’s face to feel the vibrations of speech, then touching their own faces while mimicking the movement and sound.

Paul’s father died while he was still in school. His mother moved to St. Louis to be with her son so he could still attend, but live at home. She took the opportunity to study at CID and she became an accredited teacher for deaf children. When it was time for high school, Paul and his mother moved to Houston, where she started a school for the deaf, and he enrolled in public school for the first time. Paul had no interpreter, no helper of any kind.

In a 2007 documentary made by the Taylors’ youngest daughter, Paul tells a story about an experience he had in high school. There was a nice looking girl in his class, and he wanted to know more about her, so he asked a different girl who she was. When that girl offered to give Paul the first girl’s telephone number, he stopped in his tracks, realizing at that moment how different he was because he couldn’t use the phone like all the other kids. The experience stuck with him and helped drive his life’s work.

Phones for All

After high school, Paul completed his bachelor’s of chemical engineering degree from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1962 and moved back to St. Louis to earn a master’s degree in operational research at Washington University. In the meantime, Sally, who had gone to high school in St. Louis, earned her bachelor’s degree in home economics and returned to CID to teach physical education, religion, and home economics. When Paul learned that Sally was living in town, he got in touch with her immediately. They started dating and were engaged six months later.

Paul took Sally to the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, New York for their first anniversary. They marveled at AT&T’s Picturephone and wished the future would arrive sooner so they could easily talk from anywhere by reading each other’s lips. By day, Paul was an engineer at McDonnell Douglas and later, Monsanto. He was a different kind of engineer at home, devising different ways to help raise their three hearing children. After their first child was born, Paul built a system that would blink the lights in the house to let them know the baby was crying.

He also did whatever he could to help the deaf community by volunteering his time. The phone problem still bothered him greatly. When he noticed an old Western Union teletype machine from WWII just sitting around collecting dust, he got the idea to turn it into a new kind of communication tool.

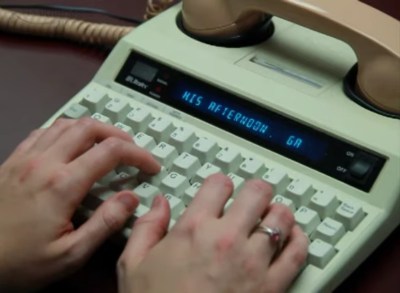

Around the same time, a deaf physicist named Robert Weitbrecht was developing an acoustic coupler that would transmit teletype signals over consumer phone lines. Paul got Weitbrecht to send him one and created one of the first telecommunication devices for the deaf (TDD). With one of these devices on each end of the phone line, anything typed on one would be printed out on the other. Paul worked with Western Union to get these old teletypewriters into the hands of hearing and speaking-impaired people, and convinced AT&T to create a relay service to use them as well.

Paul started a non-profit organization to distribute these early TDDs to other deaf St. Louisans. He asked a local telephone wake-up call service to help out, and built one of the first telephone relay systems in the process. Although both parties needed a TDD to be able to communicate, this was a big step in the right direction.

Paul also did a lot of work to keep the machines humming for the people who depended on them. Teletypewriter manuals were helpful, but were awfully dense reading material for the layman. Paul organized a week-long workshop to create a picture-rich manual called Teletypewriters Made Easy to help people repair and maintain three common models of teletypewriter. Paul discusses his personal history with TDD development in the video below.

A Loud Voice for the Deaf Community

In 1975, Paul was offered a position at the National Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology, so the Taylor family moved to upstate New York. Paul became a computer technology professor and chairman of the Engineering Support team. He stayed there for the next 30 years before retiring.

During this time, he advocated for a national, operator-assisted telephone relay service through which deaf and hearing impaired people could communicate with anyone, whether or not the other person had a TDD.

The idea was that the deaf person would use a TTY to call an operator, who would get the other person on the line and relay messages back and forth between the two parties by typing out what the voice caller said and reading aloud what the TDD user typed in response. Paul took a two-year leave of absence from teaching and worked directly with the FCC to write regulations that became part of the guidelines prescribed in the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Learning How to Hear

At the age of 65, Paul and Sally decided to get cochlear implants after a lifetime of silence. Their youngest daughter Irene made a documentary about their experience called Hear and Now, which is embedded below. It’s an interesting firsthand look into the process, which is not the instant cure that the internet may have led you to believe. The implant can’t be activated until the swelling from surgery goes down, which takes about a month. And it can take years for the brain to get used the new sensory information and begin to distinguish relevant sounds from background noise.

Although TTY/TDDs are falling out of use thanks to the videophone-enabled text messaging devices in most people’s pockets, their influence on communication lives on in shorthand now used in our everyday messages — OIC, PLS, and THX are older than you might think.

Thanks for the tip, [Zoobab].

No comments:

Post a Comment