When Paul Allen founded Stratolaunch in 2011, the hope was to make access to space cheaper and faster. The company’s massive carrier aircraft, the largest plane by wingspan ever to be built, would be able to carry rocket-powered vehicles up into the thin upper atmosphere on short notice under the power of its conventional jet engines. The smaller vehicle, free of the drag it would incur in the denser atmosphere closer to the ground, could then be released and continue its journey to space using smaller engines and less propellant than would have been required for a conventional launch.

But Allen, who died in October of 2018, never got to see his gigantic plane fly. It wasn’t until April 13th, 2019 that the prototype carrier aircraft, nicknamed Roc, finally got to stretch its 117 meter (385 feet) wings and soar over the Mojave Desert. By that time, the nature of spaceflight had changed completely. Commercial companies were putting payloads into orbit on their own rockets, and SpaceX was regularly recovering and reusing their first stage boosters. Facing a very different market, and without Allen at the helm, Stratolaunch ceased operations the following month. By June the company’s assets, including Roc, went on the market for $400 million.

Finally, after years of rumors that it was to be scrapped, Allen’s mega-plane has flown for the second time. With new ownership and a new mission, Stratolaunch is poised to reinvent itself as a major player in the emerging field of hypersonic flight.

Failed Partnerships

Stratolaunch evolved from the research and development that went into the Scaled Composites SpaceShipOne, which Paul Allen had funded to the tune of $25 million in 2004. Seeing the promise in air launched rockets, Allen teamed up with SpaceShipOne’s designer Burt Rutan to develop a carrier aircraft large enough to suspend a medium-lift rocket under its wings.

The design for the rocket itself was to be carried out by another company, and in 2011 it was announced that SpaceX would develop a four or five engine variant of the company’s Falcon 9 booster that could be carried by Stratolaunch. But within a year, the partnership had dissolved. Speaking to Spaceflight Insider in 2015, then head of Stratolaunch Charles Beames said that the goals of the two companies simply didn’t align: “We were interested in their engines, but Elon and his team, they’re about going to Mars, and we’re just in a different place.”

There were other similarly short-lived agreements with various aerospace companies to develop a rocket-powered vehicle for Roc to carry, but nothing ever progressed past the concept stage. Eventually Stratolaunch realized they would need to develop both vehicles themselves, but with all of their funding and time invested in getting the carrier aircraft ready for test flights, little progress was ever made.

By the time Stratolaunch ceased operations and put their assets on the market in 2019, they only had one half of the equation. The carrier aircraft was built and tested, but it didn’t have anything to carry.

Flying Higher and Faster

A rocket that’s been carried out of the dense lower atmosphere by an airplane doesn’t need to fight against nearly as much drag as its ground-launched counterparts, and by optimizing the engine’s nozzle for the reduced ambient pressure at higher altitudes, overall efficiency can be increased. In short, it’s easier for the vehicle to build up the tremendous speed necessary to climb the rest of the way out of the atmosphere and eventually reach orbit.

But what if getting into orbit wasn’t the goal? What if you wanted to build a vehicle capable of sustained hypersonic flight? In that case an air launch would be ideal, as the scramjet engines used to power these aircraft only start to work when the incoming air is moving at speeds of around Mach 4. That’s why previous hypersonic research vehicles like the NASA X-43 and the Boeing X-51 Waverider were air launched from the wing of a B-52 using a small booster rocket.

The company that now owns Stratolaunch, Cerberus Capital Management, believes the Roc carrier aircraft is an ideal test platform for hypersonic technology. They’re currently developing an autonomous vehicle called the Talon-A which can carry customer payloads through the hypersonic environment and then glide down to a conventional runway landing. This would allow customers to test individual components, such as sensors and avionics, at Mach 5+ speeds without having to build their own vehicle to fly them on.

As the 2,722 Kg (6,000 pound) Talon-A is far smaller and lighter than the vehicles Roc was initially designed for, up to three of them could be launched during a single flight. Each Talon-A would itself be capable of “ridesharing” several experiments simultaneously, further reducing the cost to the customer. When running at full capacity, Stratolaunch hopes to perform at least one such flight every month.

Reaching for the Stars

With increasing commercial and military interest in hypersonic engines and vehicles, Stratolaunch seems well positioned to capitalize on the next frontier of aerospace research and development. With the recent shakedown flight of the Roc carrier aircraft verifying the long grounded behemoth is still airworthy, development on the Talon-A will likely begin in earnest. The first test flight was previously scheduled for 2022, but as with many large engineering projects, it will likely get pushed back due to COVID-19.

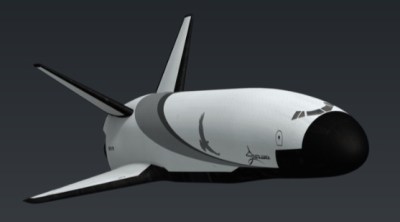

Looking ahead, Stratolaunch still hasn’t given up on Paul Allen’s original dream of air launching orbital spacecraft. The company has resurrected the concept for a reusable spaceplane that they were working on before their 2019 acquisition, this time under the name Black Ice. Little is known about this craft other than the fact that it’s intended for cargo flights to low Earth orbit and that a later upgraded version could potentially carry human passengers.

Given their track record, more than a little skepticism is probably in order when it comes to the future of Stratolaunch. But if they can really develop their own hypersonic aircraft and perform regular research flights within the next few years, the next logical step would be to take their place among the new breed of commercial spaceflight companies that Allen always believed would be the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment