Leprosy is a bacterial disease that affects the skin, nerves, eyes, and mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract. It is transmitted via droplets and causes skin lesions and loss of sensation in these regions. Also known as Hansen’s disease after the 19th century scientist who discovered its bacterial origin, leprosy has been around since ancient times, and those afflicted have been stigmatized and outcast for just as long. For years, people were sent to live the rest of their days in leper colonies to avoid infecting others.

Until Alice Ball came along, the only thing that could be done for leprosy — injecting oil from the seeds of an Eastern evergreen tree — didn’t really do all that much to help. Eastern medicine has been using oil from the chaulmoogra tree since the 1300s to treat various maladies, including leprosy.

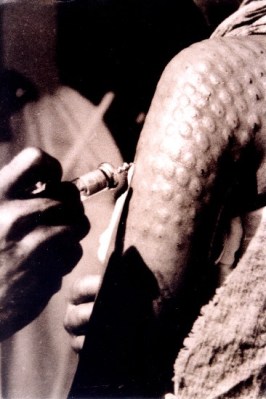

The problem is that although it somewhat effective, chaulmoogra oil is difficult to get it into the body. Ingesting it makes most people vomit. The stuff is too sticky to be applied topically to the skin, and injecting it causes the oil to clump in abscesses that make the patients’ skin look like bubble wrap.

In 1866, the Hawaiian government passed a law to quarantine people living with leprosy on the tiny island of Moloka’i. Every so often, a ferry left for the island and delivered these people to their eventual death. Most patients don’t die of leprosy, but from secondary infection or disease. By 1915, there were 1,100 people living on Moloka’i from all over the United States, and they were running out of room. Something had to be done.

Professor Alice Ball hacked the chemistry of chaulmoogra oil and made it less viscous so it could be easily injected. As a result, it was much more effective and remained the ideal treatment until the 1940s when sulfate antibiotics were discovered. So why haven’t you heard of Alice before? She died before she could publish her work, and then it was stolen by the president of her university. Now, over a century later, Alice is starting to get the recognition she deserves.

Surrounded By Chemistry

Alice August Ball was born July 24th, 1892 in Seattle, Washington. She was one of four children, with two older brothers and a younger sister. Alice’s family was middle class — her father was a newspaper editor, lawyer, and photographer. Her mother was a photographer. And her grandfather, James Presley Ball, was a famous photographer who was among the first Black Americans to use the daguerreotype method — printing photographs on metal plates instead of paper. This was the first publicly-available printing process and it involved iodine-sensitized silver plates and mercury vapors, so Alice was surrounded by chemistry from a young age.

When Alice was still a child, the family moved to Hawaii in an attempt to soothe Grandpa Ball’s arthritis with heat. He died soon after they arrived, and the family moved back to Seattle about a year later. Alice attended Seattle High School until 1910, earning high grades in all the sciences. Then she earned two bachelor’s degrees from the University of Washington by 1914 — one in pharmaceutical chemistry, and the other in the science of pharmacy.

Alice was offered several scholarships for graduate school and settled on the University of Hawaii. She received a master’s of chemistry and stayed on as a professor. Part of her master’s thesis included a study of the Kava plant species and its chemical properties. Her work drew the attention of Dr. Harry T. Hollmann, who recruited Alice to study chaulmoogra oil and to assist him in treating leprosy patients at Kalihi Hospital when she wasn’t teaching.

The Ball Method

Alice and Dr. Hollmann had been heating the chaulmoogra oil, but she realized that was the wrong approach and tried freezing the extract instead after exposing the fatty acids in the oil to alcohol. In doing this, Alice came up with a method to isolate the ester compounds from the oil and hacked them to produce a substance that could be better absorbed by the body while keeping the medicinal value intact.

The Ball Method worked quite well. Within a few years, nearly 100 people who had received the intravenous chaulmoogra oil treatment had no more lesions and were allowed to return home to their families. It was so successful that for a few years, no new patients were exiled to Moloka’i. Chaulmoogra oil continued to be used until the 1940s when sulfonamides (antibiotics) were invented.

Unfortunately, Alice died December 31st, 1916 before she had a chance to publish her work. Though her death certificate lists ‘tuberculosis’, the cause is arguably unknown. It was reported that she was accidentally exposed to chlorine gas while giving a demonstration about proper gas mask usage.

The college’s president, Arthur Dean, picked up where Alice left off and then co-authored a paper in 1920 claiming it as his own without any credit to Alice. Dr. Hollmann published his own paper two years later giving Alice the credit she deserved, and admonishing Dean for having the audacity to add absolutely nothing to Alice’s work and then pass it off as his own.

In the 1930s, the King of Siam (now Thailand) sent a chaulmoogra tree to the University of Hawaii as a thank you gift. A plaque was affixed there on February 29th, 2000 in a ceremony that was attended by several former inhabitants of Moloka’i. That day, the lieutenant governor of Hawaii declared it would be henceforth known as Alice Ball Day and be celebrated every four years. Historians have worked since the 1970s to restore Alice Ball’s legacy, and we think it’s an important one worth immortalizing.

No comments:

Post a Comment