There was a time when the idea of an international space station would have been seen as little more than fantasy. After all, the human spaceflight programs of the United States and the Soviet Union were started largely as a Cold War race to see which country would be the first to weaponize low Earth orbit and secure what military strategists believed would be the ultimate high ground. Those early rockets, not so far removed from intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), were fueled as much by competition as they were kerosene and liquid oxygen.

Luckily, cooler heads prevailed. The Soviet Almaz space stations might have carried a 23 mm cannon adapted from tail-gun of the Tu-22 bomber to ward off any American vehicles that got too close, but the weapon was never fired in anger. Eventually, the two countries even saw the advantage of working together. In 1975, a joint mission saw the final Apollo capsule dock with a Soyuz by way of a special adapter designed to make up for the dissimilar docking hardware used on the two spacecraft.

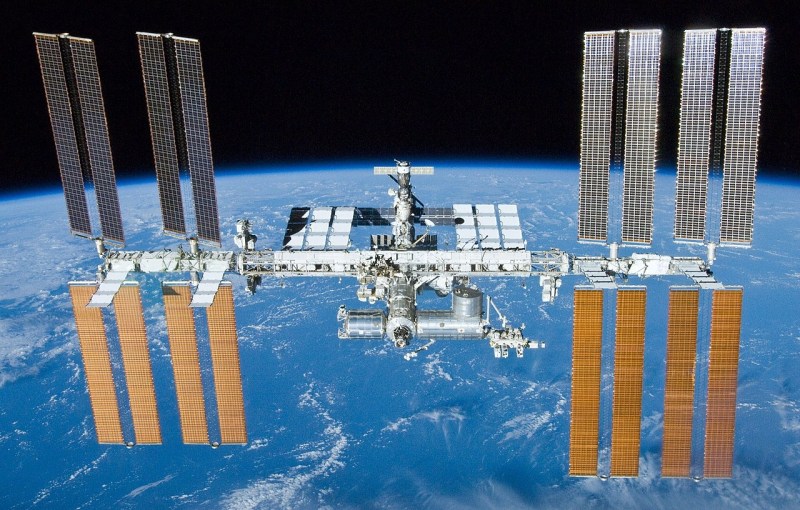

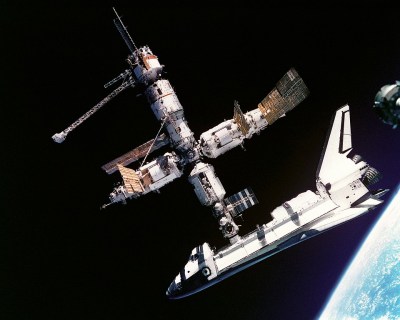

Relations further improved following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, with America’s Space Shuttle making nine trips to the Russian Mir space station between 1995 and 1997. A new era of cooperation had begun between the world’s preeminent space-fairing countries, and with the engineering lessons learned during the Shuttle-Mir program, engineers from both space agencies began laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the International Space Station.

Unfortunately after more than twenty years of continuous US and Russian occupation of the ISS, it seems like the cracks are finally starting to form in this tentative scientific alliance. With accusations flying over who should take the blame for a series of serious mishaps aboard the orbiting laboratory, the outlook for future international collaboration in Earth orbit and beyond hasn’t been this poor since the height of the Cold War.

The Station’s Wild Ride

The most recent drama started with the docking of the long-awaited Russian Nauka module on July 29th. While it was successful in the end, the process was anything but smooth, resulting in an unexpected ride for the occupants of the Station.

After more than a decade of delays and redesigns, the arrival of Nauka would have been a historic event even had things gone according to plan. With a length of 13 meters (43 feet) and a mass of 20,300 kg (44,800 lb), the new multi-purpose module dwarfed all but the Zarya and Zvezda segments that served as the nucleus of the Station during initial construction. The new module wasn’t just notable for its size, either. With the Space Shuttle no longer in service, Nauka had to fly to the ISS under its own power and perform an autonomous docking; a sharp departure from how the majority of previous modules had been transported and installed.

Despite some early glitches everything appeared to have gone according to plan, and Russian cosmonauts were preparing to open the hatches to the new module when it suddenly began firing its onboard thrusters. Preliminary investigations have determined that Nauka’s guidance computer erroneously believed it to still be in free-flight mode, and for reasons which are still not fully understood, its automated systems attempted to back it away from the Station. But with the module firmly attached to the bottom-most docking port of the ISS, Nauka’s thrusters instead begin rotating the entire complex around its center of mass.

The Station’s guidance system noticed the shift from its intended position, and attempted to compensate using the Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs). When this wasn’t enough to stop the spin, thrusters on the Zvezda module and eventually the docked Progress MS-17 resupply vehicle were commanded to fire against the direction of rotation. While initial NASA estimates claimed the Station rotated only 45° off of its intended attitude, the agency has since admitted the complex spun 540° over the course of approximately 45 minutes.

The rate of rotation was low enough that crew members reportedly didn’t notice it until notified by Mission Control, but the tug of war between the modules which was causing the highly unusual maneuver was putting the structure of the Station under stresses it was never designed for. The slow tumble was also making communications difficult, as the Station’s antennas were continuously being pulled away from their intended alignment. Zebulon Scoville, the NASA Flight Director on duty, made the determination to officially declare a “spacecraft emergency” and the docked SpaceX Crew Dragon was powered up should the crew members be ordered to evacuate.

As Scoville later explained in an interview with The New York Times, neither the crew aboard the Station nor Mission Control in Huston actually had the ability to command Nauka during the ordeal. As the module had not been fully integrated into the Station’s systems it could only be controlled from a Russian ground station, but none were in range. In the end, it’s believed that the module’s thrusters only stopped firing because they ran out of propellant.

In a scathing article published by IEEE Spectrum, former NASA engineer James Oberg said the mishap was a worrying sign that the space agency is returning to the complacent mindset that doomed Shuttles Challenger and Columbia. Specifically he questions the decision making process that allowed Russia to dock such a large and powerful module to the ISS without any provision for the crew or Mission Control to take command of it in an emergency situation, and calls for an independent investigation to determine if international politics is being given priority over crew safety.

An Explosive Accusation

In an apparent effort at damage control, Russian news agency TASS published a rebuttal to what it claimed was a systematic attempt by Western journalists to sow doubt in the country’s space program. With the support of an unnamed high-ranking official within Roscosmos, author Mikhail Kotov attempted to debunk twelve criticisms he’s identified in coverage from publications as diverse as Ars Technica and The Daily Beast.

Many of the claims have to do with funding, or more accurately, the lack thereof. But Kotov dismisses the idea that the meager budget of Roscosmos leads to shoddy engineering or limited innovation, in fact, he counters that fiscal conservatism is one of the agency’s core strengths. The article also goes on to explain the country’s efforts to replace Soviet-era facilities, spacecraft, and boosters.

The list of relatively timid quasi-official statements likely would have gone unnoticed for the most part if it wasn’t for the inclusion of an exceptionally inflammatory and completely unsubstantiated claim that the hole discovered in a Soyuz capsule during a 2018 investigation was not the product of an assembly mistake as long assumed, but a willful act of sabotage by American astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor. Quoting the anonymous official, Kotov states the first-time astronaut may have suffered an “acute psychological crisis” due to a blood clot in her neck, and that she could have damaged the Soyuz capsule in an effort to expedite the crew’s return to Earth.

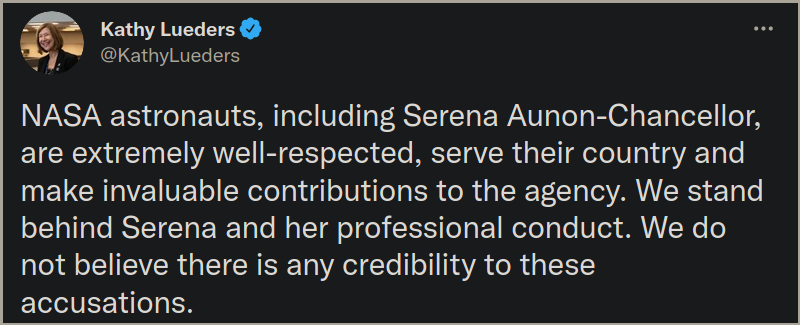

In response to this unprecedented ad hominem attack against one of their astronauts, and potentially the unauthorized disclosure of a private medical condition she may have suffered while in orbit, NASA could apparently only muster the most tepid of responses. Kathy Lueders, the head of NASA’s Human Spaceflight Program, took to Twitter to say the agency stands behind its astronauts and that they don’t believe there’s any credibility to the allegations. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson later retweeted Lueder’s message, but no official post was added to the agency’s public relations website.

When it comes to defending the reputation of Auñón-Chancellor, a woman that has dedicated more than a decade of her life to the agency, it would appear NASA believes a 37 word tweet should suffice. It’s difficult to see such a milquetoast response as anything other than the administration worrying more about the political ramifications of definitively contradicting Roscosmos than the career of one of their astronauts.

A Parting of Ways

NASA and most of its international partners have pledged to support the International Space Station until 2028 or 2030, but Russia has been hesitant to commit to extending their involvement past 2024. As recently as June 7th, Roscosmos Director General Dmitry Rogozin has been quoted as saying Russia will terminate their involvement with the ISS program in 2025 if US sanctions against the country aren’t lifted by the White House. Earlier in the year, Roscosmos also cited concerns over the age of the ISS as one of the reasons they were planning on launching a domestically-developed outpost known as the Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS) into a near-polar orbit. Its proposed course over the Earth would make ROSS an ideal platform for observing Russia and the Arctic, but puts it largely out of reach for spacecraft launching from Cape Canaveral.

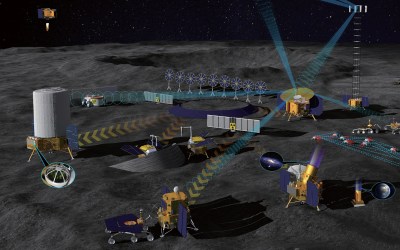

The growing rift between the countries doesn’t end in low Earth orbit, either. Despite hopes they would provide a module for NASA’s Lunar Gateway station, Russia is no longer listed among NASA’s international partners for the project. Instead, Roscosmos and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) have announced plans to construct what they’re calling the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

The robotic outpost would largely eschew human explorers in favor of advanced landers, telescopes, and highly mobile rovers. Neither country has provided a firm timeline for development and construction of the ILRS, but it’s not expected to become operational until the 2030s. Short duration human missions to the ILRS, if they happen, wouldn’t begin until closer to 2040.

While Russia will almost certainly remain involved with the International Space Station program until ROSS is operational, it seems clear that the end of the country’s scientific alliance with the United States is on the horizon. Though an improved relationship between the White House and Kremlin in the next few years could see Roscosmos contribute to NASA’s Artemis moon program in some capacity, sharing spaceflight technology with China is a line in the sand that the United States is unlikely to cross.

No comments:

Post a Comment