Burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. While most attempts to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions focus on reducing the amount of CO2 output, there are other alternatives. Carbon capture and sequestration has been an active area of research for quite some time. Being able to take carbon dioxide straight out of the air and store it in a stable manner would allow us to reduce levels in the atmosphere and could make a big difference when it comes to climate change.

A recent project by a company called Climeworks is claiming to be doing just that, and are running it as a subscription service. The company has just opened up its latest plant in Iceland, and hopes to literally suck greenhouses gases out of the air. Today, we’ll examine whether or not this technology is a viable tool in the fight against climate change.

How It Works

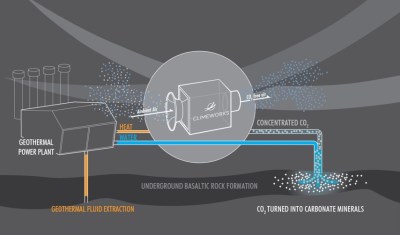

The basic theory is to capture carbon dioxide from the air, and then pump it below ground where it can be stored in a safe, stable fashion. This starts with direct-air capture: fans suck in air, and carbon dioxide is chemically trapped in a filter. Climeworks appears to use an adsorption-type filter for capturing the CO2, but details on the company’s website are sparse.

Once at capacity, the filter can then be heated to release its captured CO2 so it can be stored. The gas is mixed with water and pumped deep underground into a basaltic rock formation. Over time, the CO2 reacts with minerals to form stable carbonates.

Scientific papers have covered the concept before, with a trial in Iceland exploring the idea. In practice, 95% of the injected CO2 was successfully mineralized and stored in less than 2 years.

Is It Practical?

As with any carbon storage technology, it’s important to look at the hard data to determine whether this is a viable solution for climate change. This involves looking at not only the amount of greenhouse gas that can be stored, but also the energy required to achieve this.

In 2017, Climeworks operated a plant in Sweden (machine translation). This installation was capable of removing 900 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere per year, using the output to feed a greenhouse. The process required between 1,800 kwh and 2,500 kwh of thermal energy per ton of CO2 captured from the air. While the energy requirements may appear high, the group noted that waste heat from other industrial processes normally suffices for the energy input required.

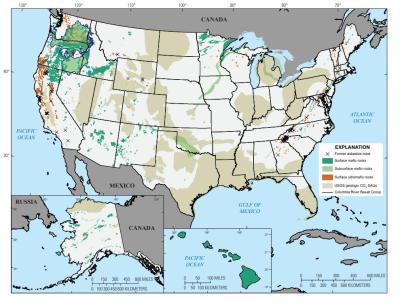

The storage part of the equation would not necessarily be as difficult; current data suggests 7000 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide could be stored off the coast of Iceland, with plenty of other geologically suitable options around the world too.

At the time, the team set a goal of removing 1% of the world’s CO2 emissions annually by 2025. Global CO2 output was estimated to be 36.81 billion tons in 2019. To remove 1% of this would take on the order of 409,000 plants operating at 900 tonnes per year. The group have been quoted that around 250,000 plants would be required by their own modelling, which presumably takes into account potentially higher emissions in 2025 and larger sequestration plants in future.

These figures are steep, and huge sums of money and land would be required to implement such facilities. As a guide, McDonalds operates just under 40,000 restaurants worldwide. It seems unlikely that, in the short space of a few years, we’ll see anywhere near 250,000 sequestration plants pop up around the world. Governments are still moving slowly on even simpler measures to reduce outputs. Similarly, many nations have delayed or simply ignored targets from international agreements made in years past.

Sequestration As a Service

Regardless, Climeworks has pressed on. Working in partnership with Icelandic company Carbfix, the company has just opened its largest facility yet in Iceland. The plant known as ‘Orca’ is intended to remove up to 4,000 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere every year. That’s roughly equivalent to emissions from 870 passenger cars based on EPA figures.

The plant cost on the order of $10-15 million US dollars to build. The company claims that the project is a stepping stone on the way to “megaton” removal capability in the second half of the decade. With facilities of this capacity, the company could hit its 1% emissions target with 92,000 plants. It’s still a ridiculous number; one that seems improbably large given the limited impact it would have on global emissions.

Assuming enough land could be found across the world, establishing the plants at those rates would cost $920 billion dollars. It’s a hefty price to pay to eliminate 1% of global emissions.

So who is going to pay for this? The Climeworks business model raises a few eyebrows, essentially offering Sequestration as a Service. It allows members of the public to offset their own carbon output, with users asked to sign up and pay a monthly subscription fee. Depending on the level chosen, the user pays a set amount to offset a certain mass of CO2 per year.

For 49 Euros a month (~$57 USD), one can pay for the capture of 600 kg of carbon dioxide per annum. Or, alternatively, the same service can be bought from reseller Tomorrow’s Air, marked up to $75 USD. As a guide, one round-trip flight from London to New York emits around 968 kg of CO2 per passenger. Shorten that to London to Rome and back, and you’re looking at around 234 kg per passenger. Climeworks boasts 8662 subscribers spread across 56 countries around the world, and claims to presently operate 15 air capture facilities at this time.

On the face of it, the subscription method appears to be an attempt to generate income for a sequestration operation from environmentally conscious individuals. It bears noting that in the company’s own FAQ, it states that the CO2 removal that subscribers have paid for will be executed “within 5 years or earlier following the subscription date.” The company provides yearly certificates to subscribers, however these only state “the amount of carbon dioxide that has been ordered for removal in [the subscriber’s] name.” However, the company does claim to be seeking third-party certification to give its operations credibility.

Overall, there aren’t huge question marks around the technology itself. Carbon dioxide can be captured from the air with adsorption filters, and it can similarly be stored using the mineralization process. The real question is whether or not it’s a viable solution to climate change in the short to medium term. Based on the present figures, it seems more likely that bigger gains could be possible from investing in other areas. For example, spending huge sums on renewable energy and grid storage would eliminate a large amount of carbon emissions in the first place, entirely avoiding the need to pull that CO2 out of the air later on.

While carbon capture and sequestration is a great idea in theory, in practice it’s simply not there yet. Capturing CO2 directly out of the atmosphere (as opposed to at the source like scrubbers at power plants) simply isn’t efficient enough or able to be executed on a large enough scale to make much of a dent in the problem. Research on the technology should continue, but don’t expect it to be the silver bullet that saves the world in the next few years.

No comments:

Post a Comment