The Atlas family of rockets have been a mainstay of America’s space program since the dawn of the Space Age, when unused SM-65 Atlas intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) were refurbished and assigned more peaceful pursuits. Rather than lobbing thermonuclear warheads towards the Soviets, these former weapons of war carried the first American astronauts into orbit, helped build the satellite constellations that our modern way of life depends on, and expanded our knowledge of the solar system and beyond.

Naturally, the Atlas V that’s flying today looks nothing like the squat stainless steel rocket that carried John Glenn to orbit in 1962. Aerospace technology has evolved by leaps and bounds over the last 60 years, but by carrying over the lessons learned from each generation, the modern Atlas has become one of the most reliable orbital boosters ever flown. Since its introduction in 2002, the Atlas V has maintained an impeccable 100% success rate over 85 missions.

But as they say, all good things must come to an end. After more than 600 launches, United Launch Alliance (ULA) has announced that the final mission to fly on an Atlas has been booked. Between now and the end of the decade, ULA will fly 28 more missions on this legendary booster. By the time the last one leaves the pad the company plans to have fully transitioned to their new Vulcan booster, with the first flights of this next-generation vehicle currently scheduled for 2022.

An Impressive Dance Card

Over the years, the Atlas V has lofted some particularly notable payloads. It sent the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on the path towards the Red Planet in 2005, and provided the initial kick that sent New Horizons on its decade-long trip to Pluto a year later. It launched the OSIRIS-REx mission in 2016, which resulted in the first NASA vehicle to successfully collect a surface sample from an asteroid.

The venerable booster has also carried the autonomous X-37B spaceplane into orbit on all but one of its missions, which do double duty as both shadowy military affairs and opportunities to perform commercial scientific research. In 2019 the Atlas V even demonstrated its crewed aspirations by carrying the first Boeing Starliner into orbit, and although the spacecraft itself failed to achieve its mission goals, the rocket performed flawlessly. Finally, it had the honor of carrying both the Curiosity and Perseverance Mars rovers.

While you could argue that most of the Atlas V’s future flights won’t have quite the historic gravitas as its previous missions, there’s certainly some very important launches in the pipeline. For example, the booster is currently manifested to carry no less than five Boeing Starliner capsules to the International Space Station by the end of 2023, with most of them being operational crew missions.

In 2022 it’s slated to launch an exciting NASA project to demonstrate reentering the atmosphere with an inflatable heat shield, and in October of this year it will launch the agency’s Lucy spacecraft that’s designed to study six so-called “Trojan” asteroids that share an orbit with Jupiter over a twelve year period.

There’s also a whole slew of communication and Earth-observation satellites it’s scheduled to carry into orbit, including at least one that’s currently classified by the National Reconnaissance Office. Amazon has also contracted nine Atlas V launches from ULA to help build out their Project Kuiper satellite constellation, which will eventually consist of thousands of satellites, and is designed to compete with Starlink from SpaceX.

A Change in the Wind

With a perfect safety record, a long list of historic accomplishments, and plenty of customers still eager to put their payload onboard, why sunset the Atlas V? The most obvious reason is cost, as the expendable booster simply can’t compete with the new generation of vehicles from commercial launch providers like SpaceX. ULA has reduced their prices in an effort to stay relevant, but a flight on the expendable rocket still costs at least $100 million. The reusable Falcon 9 on the other hand, can put nearly as much payload into the same orbit for roughly half the price.

But the price tag is only part of the problem. After all, customers like NASA are far more concerned with making sure the mission goes off without a hitch than they are in saving a few million dollars. The final nail in the Atlas V’s coffin has nothing to do with how much money it takes to put a payload into orbit, but everything to do with the engines the rocket uses to do it.

Since the introduction of the Atlas III in 2000, the Atlas family of rockets have been powered by the RD-180. This extremely efficient staged combustion engine burns liquid oxygen and kerosene, and in many respects, is considered one of the finest rocket engines ever flown. Unfortunately, it’s also made in Russia.

Politically, this is simply no longer sustainable. At various points in time Russia has threatened to stop shipping the engines to the United States, and for its part, the US Congress has imposed limitations on how many RD-180s can be imported. In 2016, partly in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea, a bipartisan agreement banned the use of Russian-made rocket engines for any national security missions beyond 2022.

Vulcan to the Rescue

Facing the loss of the extremely lucrative national security flights in 2022, United Launch Alliance had to come up with a solution. The company had considered swapping out the Russian RD-180s for a domestically produced engine, but in the end, it made more sense to create a whole new vehicle that would be more price competitive against newer rockets like the Falcon 9.

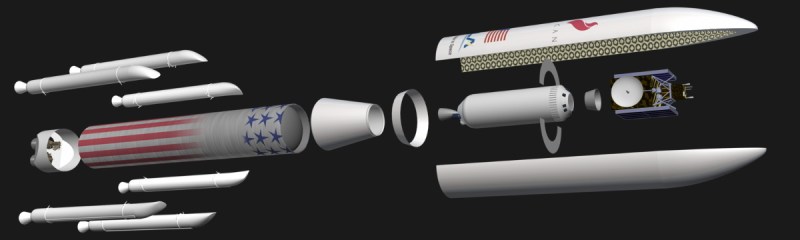

Vulcan’s BE-4 engines are being built by Blue Origin, and the relatively comparable temperatures of its liquid oxygen and liquid methane propellants has allowed the use of lighter orthogrid tanks and reduced bulkhead insulation, improving the overall mass ratio of the fuselage. While the first stage of Vulcan is projected to be only a few meters taller than that of the Atlas V, the fact that it’s considerably wider at 5.4 m (18 ft) compared to its predecessor’s diameter of 3.81 m (12.5 ft) means that the newer rocket to carry approximately 50% more propellant.

Like the Atlas V, the Vulcan supports optional solid rocket boosters (SRBs) that are attached radially around the first stage. The Vulcan will use larger versions of the GEM-63 SRBs currently flying on the Atlas V, mounted in symmetrical pairs; a departure from the unique asymmetrical booster arrangement used previously. The Vulcan will also include an upgraded version of the Atlas V’s Centaur upper stage, which ULA’s CEO Tony Bruno says will be more than twice as powerful as the current configuration.

Unfortunately, Vulcan missed the planned July 2021 date for its first launch. Construction of the vehicle itself and its associated ground support equipment has progressed well, with a prototype booster rolled out to the launch pad in August for fit and tanking tests, but flight-ready engines have yet to be delivered by Blue Origin. With the development of Vulcan’s main engine now four years behind schedule, and the 2022 cutoff date for the RD-180 fast approaching, United Launch Alliance may soon find itself even farther behind its New Space rivals.

No comments:

Post a Comment